In this ‘Trade 101’ piece, Tarlochan Lall explains in detail what leaving the European Union’s Value-Added Tax area means for business.

There has been lots of media coverage of problems at borders if the United Kingdom leaves the European Union’s customs union. But what is often forgotten are the serious implications for businesses if the UK leaves the EU’s Value-Added Tax area.

This article is the first of two parts on the implications of Brexit on the British VAT system, dealing with VAT on business to business supplies. It first looks at the current system to explain how VAT works when goods and services move to and from EU and non-EU countries, and then at the consequences of the UK leaving the VAT area, including implications of a hard Irish border. Finally some post-Brexit options are examined, including if the UK remains in the European Economic Area.

The post’s key messages are the following:

- Businesses post-Brexit are likely to face increased costs and complexity;

- Businesses will be required to account for VAT on goods exported to the EU at the time those goods cross the border, leading to potentially significant cash flow issues (though the UK government has announced that VAT on imports to the UK from the EU will remain payable at the time of the next quarterly return);

- Neither the customs union nor the European Economic Area (EEA) incorporate EU VAT rules, and as such remaining in either or both of these would not, in itself, solve the issue of cross-border VAT post-Brexit;

- Any post-Brexit simplification introduced is nevertheless unlikely to be unconditional, and may be especially burdensome for small and medium sized businesses which lack the resources to handle additional complexity.

- Keeping Northern Ireland in the the EU’s customs union would deal with customs duties: but it would not deal with VAT unless rules are introduced to keep Northern Ireland in the VAT area as well.

****

The relative lack of media coverage of VAT is surprising. Although customs tariffs/duties on goods coming into the UK vary for different categories of goods, customs duties on most goods coming into the EU are below 10% On the other hand, the standard rate of VAT is 20%.

Part of the explanation for the concentration on customs duties is that businesses paying VAT can recover it in many cases. But VAT causes cash-flow costs and costs of administrative compliance – these must not be underestimated.

How the current system works

When a supplier (“S”) is thinking about VAT, it first has to consider whether its customer is another business (“B”) or a consumer (“C”). That is because VAT works differently for business to business (“B2B”) and business to consumer (“B2C”) supplies. This part deals with B2B supplies. Part 2 deals with B2C supplies.

How VAT currently works on B2B goods and services moving across borders

- Sales of goods between EU countries

B2B Supplies of goods

Figure 1 shows what now happens when S sells £1,000 of goods B2B from another Member state to a UK buyer (“B”). S simply invoices £1,000 and charges no VAT to B. S does not have to account for the VAT to its own tax authority but must report the sale on its VAT return and keep records to show that the goods have left its country.

B, however, must keep records of the acquisition and account for the VAT to HM Revenue and Customs (“HMRC”) as if it had sold the goods to itself. So, here, it has a liability for £200 due on the sale to it by S. This is known as the reverse charge. B can claim that same VAT in its next VAT return (made every quarter) as a credit (“input tax”) (unless it makes exempt supplies, such as financial services – see below). Where B has not sold the goods in the same VAT period as it bought them, there is nothing to pay HMRC because the £200 liability is cancelled by the £200 input tax claim. But if B sells the goods to C (let us say for £1,800 including £300 VAT), VAT on that sale (£300) becomes payable at the end of the VAT period to HMRC. As the example shows, there is no cost to B as C funds the £300 which is payable to HMRC.

If B makes exempt supplies, such as financial services or health or welfare, the position is different. Businesses which make exempt supplies cannot claim back input tax on supplies they have bought for their business. In those cases, the reverse charge involves a real cost to B. On the example above £200 becomes payable to HMRC at the end of the VAT period. However, B does not have to pay or guarantee that VAT as customs duty before its goods are released so there is still a cash-flow advantage compared to customs duty (which has to be paid at the time of importation).

Where a UK supplier sells goods into the EU, the systems works in reverse. The UK supplier must keep documents to show the dispatch to the EU and file a return known as an ESL. The buyer accounts for VAT on the acquisition in their country.

- Sales of goods between the EU and third countries

Figure 2 Non-EU imports

By contrast, when goods are imported from third countries outside the EU into the UK, an import declaration must be made by B and the VAT, with customs duty (“CD”) (and VAT on the CD), must either be paid or guaranteed before the goods are released. Therefore, B either has an immediate cash-flow cost or the cost of a guarantee. Figure 2 assumes a CD rate of 5%.

If the UK leaves the EU VAT area, it will become a third country so goods moving between the UK and other EU member states will be imports and exports, as they are currently between goods moving between the UK and non-EU countries. Goods coming into the UK from EU member states will also be subject to import VAT (as well as customs declarations and customs duties if the UK also leaves the The EU’s customs union).

As far as exports from the UK are concerned, exports from the UK are zero rated so S does not have to account to HMRC for VAT on them (but can reclaim from HMRC VAT paid on goods or services used as inputs). The UK exporter must keep export documents to show the goods have left the EU (or the UK after Brexit). The non-UK importer or customer pays any duties or taxes in their country depending on any trade agreement between the UK and the country of export.

- Supplies of services to the UK

Figure 3 EU and non-EU supplies of services to the UK

Figure 3 deals with services. The position here appears to be simpler. There are normally no customs duties on services. The position for EU and non-EU cross border supplies is broadly similar for practical purposes.

But this apparent simplicity is achieved through complex rules which determine where the supplies are treated as made. For example, if a UK company obtains legal advice about a transaction in Belgium from a lawyer based in Germany, it isn’t immediately obvious where the service is supplied. The complex rules try to stop VAT lawyers having endless fun debating that sort of issue.

Although the supplier performs services wherever they actually operate (so a lawyer based in Germany usually supplies services from her office in Berlin), in the case of B2B services, as a general rule they are treated as made where the recipient is established (in the case I’ve mentioned, the UK).

In B2B supplies, the UK recipient has to treat the services as if it had made the supply to itself and by itself, and apply the reverse charge: 20% on legal services or £200 on a £1000 supply.

Non-EU purchases (say, from a lawyer based in New York) create obligations on UK business customers to account for VAT under the reverse charge. Again, the UK business has to report the purchase as a supply to itself and account for the VAT to HMRC.

The VAT reported under the reverse charge on EU and non-EU purchases of services is input tax and can be recovered in the normal way where a business can recover all its VAT. So if the UK company makes widgets, it deducts the £200 as input tax: and since the £200 reverse charge and the £200 input tax claim cancel each other out, no net amount is paid to HMRC. But businesses making exempt supplies, such as those in the financial services sector, suffer a real VAT cost: they have to account to HMRC for £200, with no input tax claim to cancel it out.

This relative simplicity can be overtaken by other complexities which may, and often do arise.

Where a business is established in its home country but the performance of services wholly or partly takes place where the customer is based, the supplier may have a fixed establishment in the country where the customer is based. If the supplier has a UK fixed establishment it has to register in the UK (there is no VAT registration threshold) and charge UK VAT. For the UK business customer, this is a domestic purchase.

There are rules for certain services which essentially have to be performed where the customer is based or involve others, such as intermediaries. They concern, for example, services related to, transport, hire services, restaurant and catering, cultural artistic, sporting, scientific, educational, entertainment and similar services. There are also special rules for certain services related to land, which are essentially treated as taking place where the land is situated. These supplies may be subject to overseas VAT, but they can also create obligations to register and account for VAT in countries where they are supplied rather than where S is established.

Where B pays VAT of an EU member country where it is not registered for VAT, B may be able to recover the VAT under procedures which exist for EU and non-EU businesses. The reclaim procedure for EU business is electronic and easier than that for non-EU businesses.

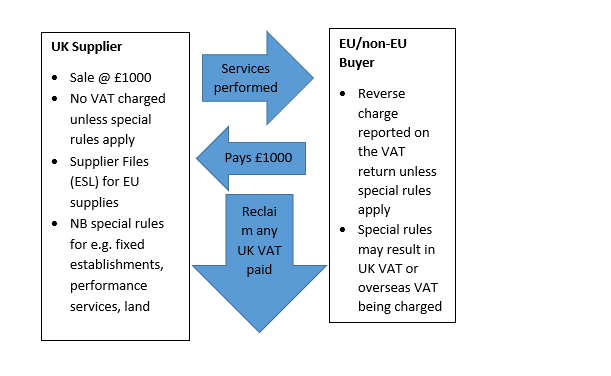

- Supplies of services from the UK

Figure 4 UK supplies of services to EU and non-EU customers

The treatment of supplies of services into the EU is the reverse of supplies to the UK. The customer accounts for VAT to its own tax authority unless special rules apply.

Supplies of services to non-EU business customers are also outside the scope of UK VAT so S does not have to account to HMRC for VAT on those supplies. Suppliers of financial services, which are VAT exempt, cannot as a general rule deduct their input tax (i.e. reclaim VAT on purchases they have made for their business): but where they supply to customers outside the EU they can deduct input tax on purchases made in order to make those supplies.

Many non-EU countries have the equivalent of VAT called, GST. GST rules in many countries impose obligations on the business customer to account for the VAT under the reverse charge. If the UK business could be said to perform services where the customer is based, they should take local advice on any obligations in that country, e.g. whether they may be regarded as having a fixed establishment there.

Under special rules, UK VAT may b chargeable on supplies made to foreign customers, for example where services related to UK land are supplied to an EU or non-EU customer. The customer may be able to reclaim the VAT under separate procedures for EU and non-EU customers.

The impact of Brexit

“One of the main concerns expressed by businesses has been that, on leaving the EU, unless the UK remains part of the EU VAT area VAT on imports from the EU will have to be paid or guaranteed for goods before goods are allowed to move through the border: VAT cannot be delayed until the relevant VAT return is filed up to four months later.

Taking the example in figure 1 for EU to UK movements, currently the position is that acquisitions from the EU are reported in the VAT return and there is no net VAT cost to S. On leaving the EU, the UK will become a non-EU 3rd country. When the goods come into the UK, they will be imports. UK businesses would move from the figure 1 example to the figure 2 example. That means that £200 of VAT will have to be paid or guaranteed to get the goods through the border. Additionally, whatever customs duties the UK adopts will also have to be paid and guaranteed. There will also be additional VAT on the customs duties.

In addition to the financial impact, there will be administrative burdens of having to make import declarations. Currently there is a system known as Customs Handling of Import and Export Freight (CHIEF). This is due to be replaced later in 2018 by a new Customs Declaration Service (CDS) as part of a modernisation programme (which was underway before EU referendum vote). The system provides for declarations to be made electronically. Although agents can be used for making the declarations, the business remains responsible for any errors. Businesses importing from outside the EU should be familiar with this: but businesses which have been involved in wholly or mainly EU trade will need to get used to this system. Brexit will therefore generate additional compliance costs.

However, the government’s ‘No Deal notice’ on VAT announced that businesses will be allowed to delay accounting for VAT on imports until they file their VAT return. That, though, does not affect the position for UK exports to the EU, where the impact outlined above will largely fall on the UK supplier’s customers, although the UK supplier will have to make necessary export declarations. The unpredictable factor for UK suppliers will be the impact on their business as a result of their customers having to bear extra burdens in purchasing from the UK as opposed another EU member state. Risks would be greater for those UK suppliers with EU competitors who can continue to make intra-EU supplies to the customers, and therefore take away business from UK suppliers. UK suppliers supplying goods on duty paid term will have real costs as they undertake to pay the duty. In that case they will have to register in the country or countries where goods are sent.

Perhaps the greatest impact will be on businesses which move components from one EU state to another as part of a manufacturing process. The most obvious example is car manufactures. They move various parts from a number of EU states to an assembly point, say in another state. There will be increased burdens for them each time the UK/EU border is crossed. Although almost all of the major manufacturers will be able to take advantage of simplification procedures available to them, they nevertheless have many smaller suppliers of components who will not be able to use the simplification procedures.

As can be seen the economic impact is potentially significant. The government is said to be exploring ways to reduce or eliminate the impact, and the measure for the postponement of accounting for VAT discussed above is one way in which it has done so. Any rules that are introduced are unlikely to be unconditional. Larger and well organised businesses may be able to cope and take advantage of simplification measures. Smaller and medium sized enterprises may have more difficulty in doing so.

On the other hand, the position of B2B services will, it seems, remain broadly the same in terms of VAT liabilities. Where a UK customer receives B2B services from abroad, VAT will still have to be accounted for by the customer under the reverse charge whether the services come from the EU or a non-EU country.

Suppliers of exempt financial services based in the EU with UK customers would benefit from the right to deduct VAT mentioned above. So UK law will have to change to retain the right to deduct for UK suppliers of financial services in order to ensure that they are not at a competitive disadvantage to their EU competitors.

Other complexities are likely to arise in the case of services. Where a UK business supplies services in the EU, they will have to consider whether they acquire a fixed establishment or otherwise need to register in such other countries where the services are actually performed.

Irish border

Avoiding a customs border between the Ireland and Northern Ireland is a hot topic. Politics aside, a border between Northern Ireland outside the EU the EU’s customs union and Ireland inside the the EU’s customs union will result in goods movements being subject to customs procedures and the payment of customs duties. VAT is often ignored here: but the VAT cost must not be underestimated as the rate of VAT is higher than most customs duties. Keeping Northern Ireland in the the EU’s customs union would deal with customs duties: but it would not deal with VAT unless rules are introduced to keep Northern Ireland in the VAT area as well. Moreover, as explained above, the key difference between VAT at an external border and VAT at an internal EU border is that at an external border VAT has to be paid on importation, not up to four months later in a VAT return.

So, unless there are specific arrangements to deal with the Irish border, movements of goods and services between Ireland and Northern Ireland would be caught by extra financial and administrative burdens. The scale of those burdens would turn on the movements between the two parts of Ireland. A briefing by the European Parliament recorded that in 2016 17% of Ireland’s exports went to the UK and represented half of its exports to the EU. In the case of Northern Ireland, one third of its EU exports went to the Irish Republic. The economic impact of an Irish VAT border would be significant.

The EU has various rules for suspending customs duties and VAT where goods come into the EU in certain circumstances. Examples are where goods transit through the EU or are intended to be re-exported, in many cases after processing. The tax and duties are essentially suspended until they reach their final destination within the EU or go out of the EU, or until some conditions for tax free movements are breached.

However, unless the UK remains part of the the EU’s customs union and the VAT area, those rules will not apply unless equivalent rules are introduced in the UK. Currently those rule apply to goods coming into the UK from outside the EU. Equivalent domestic rules will become necessary for goods moving from the EU to the UK. This point is important because such rules would be relevant for goods moving from Ireland into the UK, either for re-export or where they move from Ireland to other EU countries through the UK rather than by alternative more expensive means of moving around the UK.

One such set of rules applies for goods which transit within the EU without payment of duties or tax. There is a computerised system for monitoring the transit. When goods enter the EU but are intended for movement out of the EU, provided relevant procedures are complied with and the duties and tax that would be otherwise be payable are guaranteed, the goods can move within the EU without payment. Currently goods can move freely from Ireland through the UK to other EU countries without guarantees and customs procedures compliance. However following Brexit, such transit procedures and guarantees will be necessary for goods moving from Ireland to the UK and leaving the UK for another EU state unless special replacement rules are introduced.

These are some headline illustrations of the extra burdens that would apply, using Ireland as an example.

Options post Brexit

Assuming the transitional period is adopted, essentially until December 2020, the current treatment described above will continue. That would allow businesses time to prepare for changes that would take place on 1 January 2021. In the case of the Irish border, there are already discussions to have special arrangements effectively pushing the transitional period to 31 December 2021 for goods moving across that border.

There are separate rules for customs duties and VAT, although in the case of imports, VAT is collected as a customs duty.

The EU’s customs union

The EU’s customs union allows goods to move freely without the payment of customs duties and compliance with customs procedures. The The customs union also provides for the same tariffs, the common tariff, to be applied throughout the EU for goods coming into the EU. If the UK remains in the customs union, the advantage of free movement of goods without duties and customs procedures would be maintained. However, the UK would not be able to negotiate its own trade agreements as the The EU’s customs union takes away that freedom. Securing that freedom to negotiate trade agreements, which most commentators say would in any event take years, would come at the price of having to bear the burdens of customs duties and comply with customs procedures.

But the The EU’s customs union does not solve the VAT issues.

European Economic Area (“EEA”)

The EEA exists under a 1993 agreement between the EU, its member states and States of the European Free Trade Area (“EFTA”). The agreement applies to Iceland, Lichtenstein and Norway and the members of the EU, but not Switzerland.

There are no customs duties on goods originating in the member states of the EEA except as provided in the EEA Agreement. Therefore, some customs duties may apply. And rules of origin apply. The agreement provides for simplified customs procedures. One such simplification is a transit procedure of the kind mentioned above.

The EEA Agreement does not cover the EU’s The EU’s customs union or rules on tax. Accordingly, there is no common tariff on imports into the EEA EFTA state or a common trade policy. EEA EFTA states can enter into trade agreements with third countries. The combination of the freedom to set trade policy and significant relaxations for customs duties and administration appears to be the reason why the EEA model may appear attractive to some. The EU VAT rules do not apply so the cash-flow benefit on B2B goods moving within the EU does not apply to goods moving between EFTA countries and members of the EU. In other words, the EEA model does not solve the VAT issues either.

VAT area

The VAT area generally consists of countries which adopt common EU rules on VAT. It includes the Isle of Man but not the Channel Islands. There is no official definition of the VAT area. In 2016, the European Commission produced a communication entitled ‘An action plan on VAT: Towards a single VAT area – time to decide’ which referred to the VAT area.

As part of the single market, since 1993, member states of the EU have had common VAT rules under a temporary system. The original aim for a definitive VAT system was based on taxing cross border supplies of goods in the member state of their origin. Having established that system would not work, the objective was abandoned and replaced by a new objective to devise a system based on taxing goods in the country of their destination.

In essence the destination system will involve suppliers having to charge VAT on B2B cross-border movements of goods. This would create significant VAT cash-flow costs for businesses. VAT administration will be eased by expanding the one-stop shop introduced for B2C supplies for telecommunication, broadcasting and electronic supplies. Although EU countries will also experience change, the thinking on the destination system developed over years is at an advanced stage. Most significantly, the VAT will still be accounted for through VAT returns, not at borders as a condition of getting goods across borders within the EU. By contrast, businesses in the UK will face uncertainty over the future of the UK’s VAT system and real costs of moving goods into and out of the EU. Meanwhile, they should plan for having to deal with additional financial and compliance burdens.

No way round the VAT issue

The description above is an outline, but the complexity is self-evident. Although there is much complexity in the current system, businesses and their advisers work with it and the EU has been introducing simplifications. Brexit will result in businesses having to come to terms with new rules. It is necessary to undertake analysis of the kind above at the appropriate level of detail in order to identify issues that will arise so attention can turn to how to deal with them. Although there are rumblings from the Government that measures to ease burdens for business are being considered, businesses will need to address how these issues affect them and how they should address them.

The The EU’s customs union and the VAT area are not the same thing. There is rightly much attention on ensuring free movement of goods through customs. VAT also needs attention to ensure that businesses do not suffer financial and administrative burdens as goods move within the EU. Even if simplification is introduced, it is unlikely to be unconditional and the post Brexit system may still be disproportionately burdensome for small and medium sized businesses.

Tarlochan Lall is a barrister at Monckton Chambers.

He thanks George Peretz QC for his comments.

VAT is paid by the final purchaser only, any VAT paid on items purchased by business are deducted from that businesses final sale VAT figure as is the case right now with EU imports or purchase of goods from a UK based company.

LikeLike