Among the thousands of policy questions facing Britain after it leaves the EU is what its approach should be for geographical indications. These are names — like Melton Mowbray pork pies, Rutland bitter and Bordeaux wine — that are used to identify certain products. The UK’s policy will affect both its own and other countries’ names.

People’s views of geographical indications range from cherishing them as precious cultural heritage and commercial property, to annoyance and scorn.

What are they? And what are the decisions facing the UK? This is an attempt to explain them simply. It’s in two main parts with a small third part tacked on.

Part 1 is the basics. Part 2 looks beyond that at policy. Meanwhile the waitress above mentions 10 types of food and drink. How many are geographical indications? The answer is in Part 3 at the end.

More details can be found on the websites of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and World Trade Organization (WTO).

Part 1 Basics

What are geographical indications (GIs)?

They are names used to define both the origin and the quality, characteristics or reputation of products.

Origin is not enough. A cheese made around Roquefort-sur-Soulzon in southern France cannot be called Roquefort unless it is blue, made from sheep’s milk and meets a number of other criteria.

What do they apply to?

The vast majority of geographical indications are on food and drink, particularly wines and spirits. This is because soil and climate conditions can contribute to the products’ specific qualities.

Some countries protect other types of products as well. For example “Native Shetland Wool” (agricultural but not food) in the UK, “Swiss” watches (non-agricultural) in Switzerland, and some types of carpets and other handicrafts around the world.

Thailand would even like a service to be protected — traditional Thai massage — but internationally geographical indications are only used with goods.

Are they always place names?

Usually the terms used are place names, but sometimes they are other words associated with specific regions.

For example basmati is a long-grain fragrant rice variety and not a geographical name. However, it is associated with the Punjab regions of India and Pakistan, although its status as a geographical indication is debated (the EU doesn’t recognise it) because it is grown elsewhere too.

How do they relate to rules of origin?

This has absolutely nothing to do with rules of origin, which are about customs procedures — determining whether a product can be called “made in” a certain country and therefore should qualify for duty-free trade or other special treatment under trade agreements.

Geographical indications are a type of intellectual property, a form of “branding”, along with copyright, trademarks and others, because the products’ characteristics are the result of production techniques as well as location.

Why protect them?

Protection is intended to benefit both consumers and producers. The EU speaks of ensuring a product is “authentic” (for consumers), and providing a marketing tool to give producers “legal protection against imitation or misuse of the product name”.

Under WTO rules, the objective is to avoid misleading the public and unfair competition.

How much protection?

The bottom line for the WTO’s 164 members (including the EU and UK) is what is required in its intellectual property agreement (known as TRIPS or Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights). The agreement only sets minimum standards. It does not deal with individual names. How countries meet the standards and which names they protect is left up to them through their different legal systems.

The section on geographical indications is short. It has three parts, Articles 22, 23 and 24:

- In general (Article 22), countries have to protect geographical indications to avoid misleading the public and avoid unfair competition. By this criterion, “Californian champagne” should be fine since consumers would be clear that this did not come from the Champagne region of France. But …

- For wines and spirits (Article 23), protection is taken to a higher level — even if there is no danger of misleading the public or creating unfair competition. So “Californian champagne” is no longer valid. Except that …

- There are a number of exceptions (in Article 24). These include if a term has become generic — cheddar cheese is clearly one case since it’s been made around the world for decades, if not longer. Also an exception is when the name was registered as a trademark before the WTO’s agreement was negotiated (“grandfathering”) — Parma ham has long been a trademark in Canada, an irritant for Italians who were unable to sell Prosciutto di Parma there until recently. The EU has waged a long-running and still unresolved battle with the US over the use of “Champagne”.

When the EU negotiates for its geographical indications to be protected in other countries, part of the effort is about reclaiming names that have become generic — or more vividly to “clawback” names that have been “usurped”. Feta cheese is one case. This 73-page document is what the EU and US have agreed for wines.

Part 2 Policy

How are geographical indications protected?

The names are usually the property of groups of producers or regional or national authorities, not individual companies.

How they are protected depends on where, and this matters for the UK’s future relationships, such as how it seeks to have its own names protected abroad.

The European Union probably has the most detailed and sophisticated system. Stricter criteria apply to “protected designation of origin (PDO)” and only some products are eligible. A wider category is “protected geographical indications (PGI)”. A third, “traditional speciality guaranteed (TSG)”, emphasises the production method.

The EU’s database of wines contains over 1,700 EU geographical indications (some still being considered), and just over 1,000 from non-EU countries. Only five are British.

For spirits there are 270 geographical indications including some whose protection is being considered. Only four are non-EU. Two are British: Scotch whisky and Somerset cider brandy. Part-British is Irish whiskey made anywhere on the island of Ireland.

For other products, there are almost 1,600 “registered”, “published” or “applied for” geographical indications from both EU and non-EU countries; 79 are British.

(See also this official UK list of names. Among the foods the UK wants to protect is “watercress”.)

At the other extreme used to be Norway. A few years ago, WTO members were asked to fill in a questionnaire with some examples of geographical indications they protected. Norway said it couldn’t be sure because it used consumer protection law rather than a register of names, meaning a term would have to be in a court case to know for certain.

It managed only one possibility. “‘Hardanger’ might be a protected name,” it suggested (page 80 here). Since then, Norway has brought its system much closer to the EU’s.

Some countries use specific geographical indications laws and registers. Some use consumer protection. In the US and many others protection is by trademarks and certification marks. There are even variations of approach within the EU. The UK told the WTO that it uses common law (“tort of passing off”) for some terms and trademark law for others, although fundamentally the UK is applying EU law. (See the annex in this now out-of-date WTO document.)

What does the UK face with the EU?

In theory, when the UK leaves the EU it will be free to decide how it protects geographical indications and which names to protect, so long as it complies with the WTO principles.

Will the UK move away from the EU’s near-obsession with geographical indications? It might not have too many wines, but it does have Scotch whisky and a lot of food products.

Its hand might also be forced by its future relationship with the EU. Geographical indications have always been a priority for the EU in its free trade negotiations and the EU has already demanded protection to continue in the UK after Brexit.

This is likely to mean the UK setting up its own lists of protected geographical indications with associated legislation.

What does the UK face with other countries?

Beyond the EU, the world of geographical indications has sometimes been described as a divide between old world countries, with traditional methods and products they want to protect, and the new world whose immigrant populations brought those techniques with them. It’s a bit more complicated than that. For example Taiwan is in the so-called new world group and some US producers now want protection for their own products, from wines to Idaho potatoes. But there is some truth in it.

In negotiations with some countries such as other Europeans, India and so on, the UK will be under pressure to protect their names. With others such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the US and some Latin American countries, the UK may be the one making the most demands to protect its names.

If it continues to protect EU geographical indications, Britain may need to tread carefully with the GI-sceptical “Anglosphere” countries. For example in its free trade talks, the UK might be under pressure to allow imports of Australian feta cheese (and it might want to make its own too).

The EU has deals on geographical indications with other countries, either as part of free trade agreements or separately. With Brexit, the UK wants to roll the EU’s free trade agreements over into its own, and may want to do the same with the deals on geographical indications. To do that will require either negotiation with the other countries or confirmation by them.

What does the UK face in the WTO?

The WTO agreements signed in 1994 included a commitment to set up a multilateral register for geographical indications of wines and spirts. Almost a quarter of a century later, members still have not agreed on how to do this.

The EU and its allies want the register to have some legal effect: if a name is on the register, then that should have some legal implications in all WTO members. The US and its allies see the register as little more than a database of information, which countries would be free take into account (or to ignore) when they decide whether to protect a particular name.

A second issue is whether to give some or all other products the same higher level of protection as is now given to wines and spirits (Article 23), and presumably to include them in the multilateral register. This is often called “extension”: extending the higher-level protection beyond wines and spirits.

Although this has been discussed at length in the WTO, members still have not even agreed whether it is officially a negotiation. A large number of countries support the move, but in some cases for complex bargaining reasons. The US, Australia and so on oppose it on the grounds that it would be too burdensome and restrictive, and that the standard level (Article 22) is good enough.

The UK will have to decide how to approach these questions, and also the WIPO treaties on geographical indications.

Some GI titbits

Geographical indications are complicated. Every argument has a counter-argument so they are a perfect playground for intellectual property lawyers, as the endless and bottomless debates in the WTO show. Here are some illustrations.

“-style”? Or “-method”? If “Bulgarian yoghurt” can only be made in Bulgaria, what about “Bulgarian-style” yoghurt? One view is that this is a useful indication of what the product is, helping rather than confusing consumers.

Against that is the argument that “Bulgarian-style” has no owner and no definition. The term could be abused. The reputation of yoghurt associated with “Bulgaria” would be damaged, hurting both consumers and genuine Bulgarian producers. The poor reputation of parmesan cheese made outside Italy is a real-life example.

After all, one of the features of geographical indications is that they have owners responsible for maintaining the quality and reputation. The loose term “Bulgarian-style” would not have that.

Orange: homonyms and more. Several places could have the same name, or names that sound the same (homonyms). The WTO agreement broadly covers that, but homonyms can still get pretty complicated. In late 2000 Australia entertained WTO delegates with an analysis of “Orange”. It’s a place name on five continents, some with vineyards producing what could be called “Orange wine”. And then there’s wine made from oranges. Orange is also a colour and a phone company’s trademark. It’s linked to words in other languages, including Persian where the fruit is named after Portugal, and so on. (See page 6 of this.)

Champagne: Swiss and Indian. A small village in northern Switzerland is called Champagne. It used to produce a still white wine with the name, but not since 2005. Pressure from France put an end to that. Meanwhile, in the WTO debate on “extension”, a US delegate once remarked wryly that Darjeeling tea, a claimed geographical indication, is advertised as “the champagne of teas”.

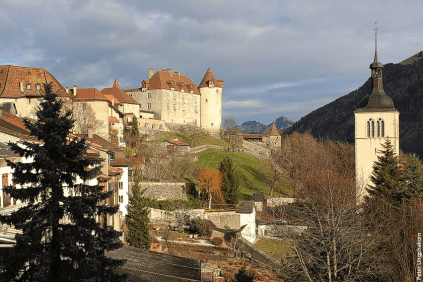

Gruyère. Gruyère is a region in Switzerland surrounding the medieval village of the same name. The cheese was first made there in 1115. It’s now been produced elsewhere for generations and the name has become generic, sometimes using “Gruyère” or an equivalent in another language.

Gruyère is not in France. Nevertheless, France has managed to register “French Gruyère” produced in a dozen departments as a protected geographical indication in the EU. Despite the stereotype of Swiss cheese, authentic Gruyère has no holes. But the French version does: it “must have holes ranging in size from that of a pea to a cherry”, according to the EU regulation.

In Switzerland, “Le Gruyère” now has a Swiss protected appellation of origin (AOP) covering four whole cantons and parts of a fifth.

But is it protected in the EU? The 2011 bilateral agreement between Switzerland and the EU says it is, along with a number of other Swiss products. As an illustration of how complicated these names can be, in the agreement, Switzerland and Greece also promise not to translate “graviera” (γραβιέρα) as “gruyère” and vice versa.

However there seems to be no internal EU law or regulation confirming this — not yet anyway — and nothing Swiss appears in the “DOOR” database of products other than wines or spirits. We can only assume the bilateral agreement holds.

On a much smaller scale than the EU, Switzerland has also been trying to “reclaim” terms that have become generic. In 2013 it secured US registration for “Le Gruyère” as a certification mark (similar to trademark). But a joint application by French and Swiss producers to protect just the word “Gruyère” in the US has been challenged and remains unsettled.

Feta. This is one of the most-debated names in the WTO. The minutes of this meeting contain 14 pages of debate in which “feta” appears 50 times. Similarly for these meetings. Is it eligible for protection? Is it generic? Where exactly is its origin? Greece, Bulgaria, Denmark even? Is the legal situation in the EU contradictory? Should migrants to Australia be allowed to continue to use the name for the cheese that their ancestors made? Is feta actually produced in Australia by immigrants or by large companies?

Still have an appetite? In 2005, the WTO Secretariat summarised the debates on “extension” in the organisation in a 44-page 21,000-word paper. Heavy going but essential reading for anyone wanting to dig deep into the subject. You can also download this 232-page guide from the International Trade Centre. Either way, keep a good Irish whiskey or Spišská borovička at hand.

Finally, Part 3, what the waitress said

At the top of this article, the waitress refers to 10 types of food and drink (not counting the general “lamb” and “cheese”). Some are geographical indications, some are not:

Geographical indications protected in the EU and therefore the UK — Cornish pasty; Tiroler Bergkäse; Caerphilly; French Gruyère; Amarone della Valpolicella; Armagnac

Names that are generic in the EU/UK — Gruyère (from Switzerland and anywhere else except parts of France); Cheddar (except “West Country Farmhouse Cheddar cheese,” which does include the original Cheddar area in Somerset, and “Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar”, from over 1,000 km away)

Not geographical indications in the EU/UK — New Zealand lamb (although “Scotch lamb” is); Evian (Evian is a place, a lakeside French town at the foot of the Alps, but the name is a trademark for bottled water)

I believe this site has got some real excellent info for everyone :D.

LikeLike